The Future is Circular: A practical framework for designing circular products

I believe the future is circular. Not as a trend, not as a marketing angle—but as a fundamental reorientation of how we design, make, and value the things we bring into our lives. Circularity asks us to slow down, to pay attention, and to take responsibility for the full story of a product—from where it begins to where it ends.

As an apparel and product leader, I help brands make sustainability-related decisions every day. And over time, the word sustainability itself has become increasingly diluted. Almost anything can be framed as “more sustainable” when compared to the deeply extractive norms our industry operates within.

Take recycled polyester from plastic bottles, for example. It’s often positioned as a sustainable solution—and in some comparisons, it is. Breaking down plastic bottles into pellets and spinning them into fiber can be less impactful than producing virgin polyester. But context matters. Using those bottles again as bottles often prevents additional plastic production, reduces energy use, and helps limit microplastic pollution. When we look at textile-to-textile recycling instead, the logic shifts entirely. The claim that bottle-derived recycled polyester is inherently sustainable doesn’t fully hold up when examined through a systems lens.

This is where circularity—and circular systems—offer a more balanced framework. Circularity isn’t about optimizing one material choice in isolation; it’s about designing systems that are less extractive by default. Systems that consider material flows, use phases, and end-of-life outcomes together, rather than treating impact as a single metric.

Much of the current conversation around circularity—especially in fashion—focuses on what happens after a product already exists, even though the greatest opportunity lies upstream, in how products are designed from the start.

This article is about grounding the conversation. Building shared language. Naming what’s broken—and what’s possible—when we move away from extractive systems and toward regenerative ones.

Circularity as a Practice, Not a Claim

Circularity itself isn’t the problem—it’s how the industry often narrows it.

In fashion, circularity is frequently reduced to a limited set of actions: recycled materials, resale, repair. These efforts matter, and they are part of the solution. But they are only fragments of a much larger system. When circularity is framed primarily through downstream fixes, we risk missing the deeper design responsibilities that determine impact long before a product is worn, resold, or recycled.

Circular systems are not defined by labels or singular interventions. They are defined by evidence, accountability, and design intention. When examined through a circular lens, greenwashing is often exposed—not through criticism, but through a lack of evidence across the system.

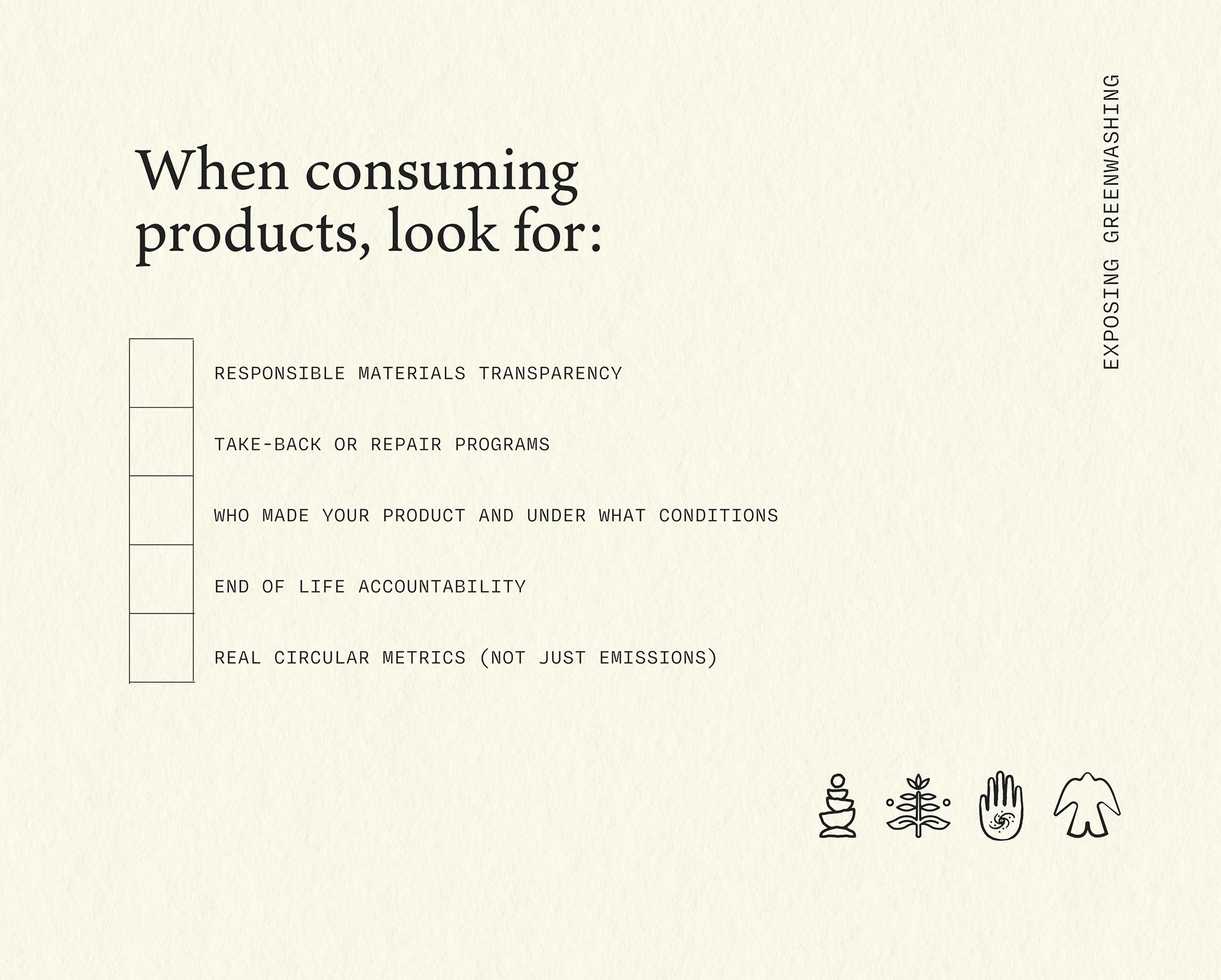

True circularity requires transparency. It means asking uncomfortable but necessary questions:

Where did this material come from?

Who made this product, and under what conditions?

What ecosystems were impacted along the way?

And when this product is no longer useful—what happens next?

If those answers aren’t clear, circularity hasn’t yet been achieved—it’s still aspirational.

Language, Systems, and Why Precision Matters

One of the reasons circularity struggles to take hold in practice is language. Vague claims and shorthand have become so common that they often preserve business as usual rather than challenge it. In Real Circularity, this phenomenon is described as “sustaina-babble”—well-intentioned language that sounds progressive but lacks the precision required for real change.

Circularity demands clearer questions and more exact answers. Not just what a product is not, but what it is—materially, chemically, socially, and systemically.

This is where whole-systems thinking becomes essential. Every product exists within nested systems—materials, supply chains, labor, ecosystems, and economies. As the book puts it, “everything is in everything is in everything.” A decision made at the fiber level ripples outward, influencing water, soil, workers, waste streams, and future options for reuse or recovery.

It’s also why not every closed loop is a healthy one. Circularity without material safety, regenerative intent, or end-of-life responsibility can still be unsustainable. Loops can be degenerative. Recycling can downcycle harm. Design choices made without systems awareness simply shift impact elsewhere.

Foundational frameworks like cradle-to-cradle design and certification have long emphasized this point: circular products must be intentionally designed for safe cycling, material health, and continued value—not just collected at the end. That upstream mindset has deeply influenced how I think about circularity today.

Being part of the Real Circularity community has reinforced something hopeful: there are people and companies actively choosing to build this way from the start. They are asking better questions earlier, accepting complexity, and iterating toward systems that work more like nature—connected, regenerative, and accountable.

Why I Wrote the Circular Standards

I wrote the Circular Standards because circularity shouldn’t be inaccessible, abstract, or reserved for specialists.

Much of the existing research, certifications, and frameworks around circularity are rigorous—and necessary—but they’re often complex, fragmented, or difficult to translate into everyday decisions. As someone working directly in apparel and product development, I saw a gap between knowing what circularity requires and actually being able to apply it when designing, sourcing, or evaluating products.

The Circular Standards were created to bridge that gap.

They are not meant to replace existing research or certification systems. They are meant to simplify them—distilling years of circular design thinking, material science, and systems research into a clear, usable framework that brands, builders, and consumers alike can understand.

Circularity works best when more people can participate in it.

By translating complex ideas into practical principles, the goal is to make circularity something you can recognize, question, and move toward—without requiring perfection or expertise. Progress happens when expectations are clear and shared.

When writing these, I tapped my very talented friend Paris Karstedt. I was swimming in research and ideas and couldn’t simplify or distill them as needed. In one day, she took everything I had been working on and distilled it into a simple framework I could use moving forward.

The Circular Standard™ — A Framework for Accountability

These four standards aren’t aspirational—they’re practical. Together, they form a clear framework for evaluating what actually qualifies as circular, and for assessing products, systems, and brands with consistency and accountability.

1. Traceable by Design

Trust is built through evidence, not claims.

Every product should be traceable from raw material to finished good. That means knowing where materials come from, who processes them, and where final construction happens. Transparency protects people, animals, and ecosystems—and prevents greenwashing disguised as sustainability.

Circular systems depend on visibility. If we can’t see the full journey, we can’t hold anyone accountable.

This is increasingly becoming a legal requirement. In the European Union, the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) introduces Digital Product Passports—digital records that carry verified information about a product’s materials, origin, durability, repairability, and end-of-life pathways. These passports are designed to make traceability and transparency a baseline expectation, not a voluntary disclosure.

2. Materials Matter

What something is made of matters just as much as how it looks.

Materials account for nearly 90% of a product’s environmental and human impact. That’s why surface-level claims aren’t enough. Recycled doesn’t automatically mean safe. Organic doesn’t always mean land is being cared for in ways that support long-term carbon sequestration. Natural doesn’t automatically mean sustainable.

True evaluation looks deeper—at sourcing, processing, dyes, finishes, water and energy use, and chemical inputs. Circularity demands materials that support ecosystems and human health, not undermine them.

This is why I’ve started documenting materials more rigorously and why, when evaluating dyes and finishes, I look to established frameworks like bluesign® and cradle-to-cradle certification to understand which chemicals and processes to avoid.

3. Interconnected Impact

Nothing exists in isolation.

Circularity recognizes that people, animals, and ecosystems are interconnected. Harm in one area ripples outward. That’s why regenerative systems matter—systems that restore soil, respect labor, protect animals, and strengthen communities.

A product should offer benefits beyond the end user. Otherwise, the cost is simply being displaced.

Certifications can be useful signals here—but they are not the full story. Social standards such as WRAP, SA8000, ISO-aligned management systems, Fair Trade, and OSHA-related workplace requirements help establish baseline protections around labor conditions, health, and safety. Environmental and animal-welfare standards like Responsible Wool Standard (RWS), regenerative agriculture frameworks, and ecosystem-based certifications aim to safeguard land, biodiversity, and animal wellbeing.

These frameworks provide important structure, but they don’t replace human relationships or local context. We can’t rely on certifications alone to prove healthy systems. Fair-trade frameworks, for example, have at times left skilled artisans underpaid for their experience. Averie Floyd, Flory Perez, and Majo Saenz’s work on dignified wage standards in Guatemala highlights why context-specific, relationship-based approaches—and ongoing engagement—are essential.

4. Waste Reduction & End-of-Life Accountability

The future cannot be built on disposability.

Circular products are designed for longevity—made to be worn longer, repaired, reused, resold, recycled, or safely returned to the earth. End-of-life is not an afterthought; it’s a design requirement.

Blended fibers that can’t be recycled. Toxic finishes that prevent composting. Planned obsolescence disguised as innovation—these are system failures, not consumer ones.

We also have to look at volume. Small-batch production and producing less, more intentionally, are critical levers. Reports from regions like Nepal and India show staggering levels of unsold and discarded textiles—evidence that overproduction itself is a design flaw.

This responsibility is increasingly being formalized through policy. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) frameworks under EU waste legislation require brands to take responsibility for products beyond the point of sale, including financing and operating take-back, reuse, and recycling systems. France’s AGEC law has accelerated this shift for textiles.

Similar changes are underway in the United States. California’s Responsible Textile Recovery Act establishes mandatory producer-funded take-back and recovery programs for apparel and textiles—making brands responsible for what happens to products after sale, not just how they are marketed.

Why I’ll Keep Writing About This

Writing is how I slow things down enough to see clearly.

In a world optimized for speed and consumption, circularity asks us to pause—to learn, unlearn, and choose with intention. By writing about circular systems, materials, and accountability, I hope to make these conversations more accessible—and more honest.

This isn’t about perfection. It’s about progress rooted in knowledge.

A Living Conversation

These posts will continue to evolve—exploring materials, systems, failures, breakthroughs, and the uncomfortable gray areas in between. Circularity is not static, and neither is my understanding of it.

If the future is circular, then learning must be too.

Born from idealism. Driven by nature. Designed for change.